Sweets for tea

I’m obsessed with Japanese sweets. Particularly obsessed with making pure white sweets, which I have not yet mastered.

The main ingredient in all the sweets is a bean paste called An. It can be made with red azuki beans or with white lima beans, or any large white bean. When you add sugar to the bean paste, it turns an off-white. Perfect for coloring.

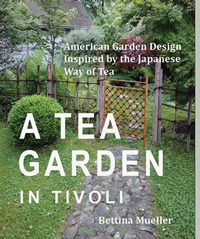

You can make all sorts of shapes with marvelous colors. I write about this more in detail in my cookbook The World in a Bowl of Tea which you can order online here.

But this is the sweet with it’s pure white that I cannot yet master. It involves making a glutinous mochi mixed with the An. So beautiful and illusive!

The aesthetics of beauty in the natural and immediate – Wabi and Sabi

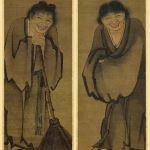

Sixteenth century Japanese Tea masters were connoisseurs of Chinese objects. In their tea gatherings they used highly prized ceramics made with the most sophisticated techniques in all of history; the 11th century Sung Dynasty ceramics were perfect in form and color. The oxblood and apple green glazed bowls and vases were flawless.

Longquan kiln between 1127-1279 (the South song era)

Sen no Rikyu, a Tea master influenced by Zen Buddhism, was the first to define a new aesthetic called Wabi. It was characterized by the crude, rough pottery wares of Japan at the time.

Wabi is the beauty of the simple, of restraint, of imperfection. It’s the beauty found hidden beneath the surface of things.

A spare room with a single vase of flowers can be wabi. The winding path through a garden of moss and shade can be wabi. Tea served in a black hand carved ceramic bowl can be wabi.

Poignant seasonal moments can also be felt as wabi. The first geese flying south in the autumn. The new buds in spring peeping out from the snow.

Another Japanese aesthetic often combined with Wabi is the term Sabi. Many people say that something is very “wabi-sabi,” but the two words mean different things.

Sabi can be defined as antique elegance. It’s found in the patina from a silver spoon worn around the edges or a 13th century cosmetic case burnished with care and now used to hold incense. The visible effects of time is deeply appreciated and there’s an emotional reaction to a piece that has been handled, loved, and used.

Wabi and Sabi are words that are used too often. They are not catch phrases. Instead, they could almost be described as a hidden philosophy about unity and harmony.

Dai Bosatsu Zendo

Sei Shonagon wrote this poem and it makes me think of Dai Bosatsu monastery.

“Count each echo of the temple bell

As it tolls in the evening by the mountain’s side.

Then you will know how many times

My heart is beating out its love for you.”

That’s me on the left. Morning service with the Roshi at Dai Bosatsu so many years ago.