Ranjatai Incense

I searched all over Kyoto to find the same incense that had been given to me years before on my birthday. The delicate fragrance had scents of sandlewood, spices of cinnamon and clove, and camphor.

In the practice of tea, incense is prized and at some tea gatherings the host will bring out various incense for the guests to appreciate. It’s called “Listening to incense.”

The most highly prized and rare incense is called Jin-koh, also called Agarwood, that comes from Southeast Asia. It’s literally worth it’s weight in gold. Agarwood forms when Aquilaria trees become infected with mold and the tree develops a resin to protect itself. This resin forms in the heartwood of the tree and is what is prized as Agarwood or Aloeswood.

The largest piece of Jin-koh in Japan was given to Emperor Shomu (AD 724-748) as a tribute from China. It has been kept in the Imperial treasure repository since that time. It is named Ranjatai and is the most famous chunk of wood on the planet. It weighs 11.6 kilograms and is 1.56 meters long.

For the past millennium, only a few small pieces have been cut from the Ranjatai.

For the past millennium, only a few small pieces have been cut from the Ranjatai.

In 1465, one small piece was ordered by Emperor Gotsuchimikado as a gift to Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. In 1574, a small piece was given from Emperor Oogimachi to general Oda Nobunaga for his efforts in unifying Japan, In 1602, Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was powerful and influential enough, obtained a piece, and in 1877, Emperor Meiji asked for a piece.

That’s how coveted this piece of wood is.

Nobunaga kept his small piece and then gave fragments of it to two guests who came for a tea gathering. This gift demonstrated his cultural superiority and power. The two guests received Ranjatai fragments presented on open fans. The fans were decorated with cut gold foil.

Every ten years Ranjatai is brought out of the treasury repository and exhibited. People line up for hours to view it – the most famous piece of incense in the world.

Red Hot Stove

On the red hearth, one flake of snow

I love the image of a flake of snow that’s landed on the red hot stove. Gone in an instant. This phrase is from a koan in the Blue Cliff Collection, Case 69 Nansen Draws a Circle.

Three Zen friends were on their way to pay respects to the National Teacher. At one point they stopped, and Nansen drew a circle on the ground and said, “If you can speak, we’ll go on.” The story tells the various responses from his friends.

What I love about this story is the introduction to the koan by Engo. He says, “Patchrobed monks who have passed through the forest of prickly briars are like snow on a red hot oven.”

The briars and thickets are my likes and dislikes, my questioning of right and wrong, good and bad.

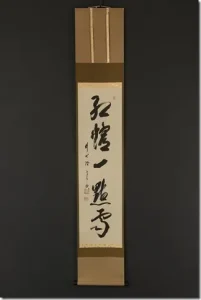

In Japanese the phrase is”Koro itten no yuki.” Here it is on a scroll.

Yamada Koun commentary:

“The forest of prickly briars” refers to our own concepts and thoughts which catch us up constantly, depriving us of our freedom. Man may be “the measure of all things” because our ability to think gives us supposed dominion over the rest of nature. But, from another standpoint, this very ability to think is the source of all our suffering.

The patchrobed monks (it need not be just monks!) who have passed through this forest of prickly briars (through the practice of Mu or Shikantaza, for example) are “like snow on a red hot stove.” If a pinch of snow were placed on a red hot stove, it would immediately melt and evaporate. In the same way, when you stand up, there is just that standing, with nothing else remaining.

All other concepts have disappeared like snow on a red hot stove.

And when you sit down, there is just that sitting, without a trace of standing left over.

Every moment of our lives is like this. Just that moment.

Each second disappears like snow on a red hot oven. Standing, sitting, eating, sleeping, laughing, crying.

The content is always completely empty.

Sweets for tea

I’m obsessed with Japanese sweets. Particularly obsessed with making pure white sweets, which I have not yet mastered.

The main ingredient in all the sweets is a bean paste called An. It can be made with red azuki beans or with white lima beans, or any large white bean. When you add sugar to the bean paste, it turns an off-white. Perfect for coloring.

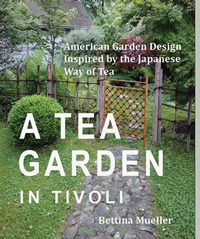

You can make all sorts of shapes with marvelous colors. I write about this more in detail in my cookbook The World in a Bowl of Tea which you can order online here.

But this is the sweet with it’s pure white that I cannot yet master. It involves making a glutinous mochi mixed with the An. So beautiful and illusive!