Ranjatai Incense

I searched all over Kyoto to find the same incense that had been given to me years before on my birthday. The delicate fragrance had scents of sandlewood, spices of cinnamon and clove, and camphor.

In the practice of tea, incense is prized and at some tea gatherings the host will bring out various incense for the guests to appreciate. It’s called “Listening to incense.”

The most highly prized and rare incense is called Jin-koh, also called Agarwood, that comes from Southeast Asia. It’s literally worth it’s weight in gold. Agarwood forms when Aquilaria trees become infected with mold and the tree develops a resin to protect itself. This resin forms in the heartwood of the tree and is what is prized as Agarwood or Aloeswood.

The largest piece of Jin-koh in Japan was given to Emperor Shomu (AD 724-748) as a tribute from China. It has been kept in the Imperial treasure repository since that time. It is named Ranjatai and is the most famous chunk of wood on the planet. It weighs 11.6 kilograms and is 1.56 meters long.

For the past millennium, only a few small pieces have been cut from the Ranjatai.

For the past millennium, only a few small pieces have been cut from the Ranjatai.

In 1465, one small piece was ordered by Emperor Gotsuchimikado as a gift to Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. In 1574, a small piece was given from Emperor Oogimachi to general Oda Nobunaga for his efforts in unifying Japan, In 1602, Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was powerful and influential enough, obtained a piece, and in 1877, Emperor Meiji asked for a piece.

That’s how coveted this piece of wood is.

Nobunaga kept his small piece and then gave fragments of it to two guests who came for a tea gathering. This gift demonstrated his cultural superiority and power. The two guests received Ranjatai fragments presented on open fans. The fans were decorated with cut gold foil.

Every ten years Ranjatai is brought out of the treasury repository and exhibited. People line up for hours to view it – the most famous piece of incense in the world.

Sweets for tea

I’m obsessed with Japanese sweets. Particularly obsessed with making pure white sweets, which I have not yet mastered.

The main ingredient in all the sweets is a bean paste called An. It can be made with red azuki beans or with white lima beans, or any large white bean. When you add sugar to the bean paste, it turns an off-white. Perfect for coloring.

You can make all sorts of shapes with marvelous colors. I write about this more in detail in my cookbook The World in a Bowl of Tea which you can order online here.

But this is the sweet with it’s pure white that I cannot yet master. It involves making a glutinous mochi mixed with the An. So beautiful and illusive!

The aesthetics of beauty in the natural and immediate – Wabi and Sabi

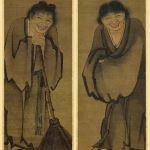

Sixteenth century Japanese Tea masters were connoisseurs of Chinese objects. In their tea gatherings they used highly prized ceramics made with the most sophisticated techniques in all of history; the 11th century Sung Dynasty ceramics were perfect in form and color. The oxblood and apple green glazed bowls and vases were flawless.

Longquan kiln between 1127-1279 (the South song era)

Sen no Rikyu, a Tea master influenced by Zen Buddhism, was the first to define a new aesthetic called Wabi. It was characterized by the crude, rough pottery wares of Japan at the time.

Wabi is the beauty of the simple, of restraint, of imperfection. It’s the beauty found hidden beneath the surface of things.

A spare room with a single vase of flowers can be wabi. The winding path through a garden of moss and shade can be wabi. Tea served in a black hand carved ceramic bowl can be wabi.

Poignant seasonal moments can also be felt as wabi. The first geese flying south in the autumn. The new buds in spring peeping out from the snow.

Another Japanese aesthetic often combined with Wabi is the term Sabi. Many people say that something is very “wabi-sabi,” but the two words mean different things.

Sabi can be defined as antique elegance. It’s found in the patina from a silver spoon worn around the edges or a 13th century cosmetic case burnished with care and now used to hold incense. The visible effects of time is deeply appreciated and there’s an emotional reaction to a piece that has been handled, loved, and used.

Wabi and Sabi are words that are used too often. They are not catch phrases. Instead, they could almost be described as a hidden philosophy about unity and harmony.

Crimson colors

Sei Shonagon sometimes gets irritated with those who wear unsuitable things like “crimson skirted trousers” at the wrong time. And then at times she loves “a white coat worn over a violet waistcoat.”

Fabric has always been important in Japan. Today in Kyoto you can visit the shop of Kitamura Tokusai who will bring out sample after sample of old and ancient fabrics that are now used in the tea ceremony to hold a tea bowl in hand. They are called Kobukusa and are much admired. Dazzling and splendid.

Not being comfortable

Tea practice, a Zen art, has always been a challenge. From the first time I learned how to fold a silk square of fabric into an elegant wiping cloth there has always been something new to wake me up – challenge me in unexpected ways.

The art of the gathering is the appreciation and deep respect for the objects whether they be new or old or ancient or with provenance.

My new tea bowl by Kouichi Osada

Today was a first for me. I was totally unsettled by a guest who is a ‘professional’ potter. With my new precious tea bowl in her hands she put the first and second digits of her fingers into a slingshot and slung her nail hard into the side of the bowl. WHACK.

“Oh, don’t do that!” I said. What was she thinking? Was she testing the validity of the glaze or the way in which it was fired? I don’t know. The bowl could have been shattered.

I’m trusting that my tea bowl will be ok.

But imagine if the bowl had survived hundreds of years and you had the honor to hold it in your hands marveling at the beauty of it and the many generations that had taken care of this fragile pottery and then someone comes along and WHACKS it. Just so they could.

I still can’t get over this. Maybe in time…