Wind and the chimes

It was early summer and cold. The window of the Tea House was opened just a crack and the wind was fierce and strong. It kept blowing the wind chimes that hung outside from the eve of the roof.

It was early summer and cold. The window of the Tea House was opened just a crack and the wind was fierce and strong. It kept blowing the wind chimes that hung outside from the eve of the roof.

They were loud and harsh, not like their usual soft, tonal chiming. It was distracting. I wanted the peaceful silence, the bird song, the sound of squirrels jumping on the roof.

Then I realized that I could use that distraction to come back to my breath. It seems so obvious now. It’s something we always practice in zazen. Come back to the breath. Count from one to ten, then back again.

Even though I’ve been practicing this for over thirty years – it was new. I realized that everything could be a reminder to come back to the present, even things that are difficult. At once, I felt grateful for everything. I felt that everything supported my life: the discordant bells, the birds, the sound of the train, traffic from the road, the laughter of kids playing next door.

Zazen is always new and full of surprises – to be more accurate, this life is always new and full of surprises.

The great Zen master Hakuin had a similar experience. He was sitting in a place like the Tea House. He had been sitting for five days for sesshin. His mind was lucid and quiet. It was an early dawn morning, the light was dim, and he heard the crows outside waking up. When the temple bell rang he realized, “That ringing. That ringing! That is me ringing! That is me ringing!

His still and clear mind had been pierced through by the bell’s sound, and that and every moment was full of deep wonder.

Less is more

My neighbor is moving and invited me over to look through boxes of free stuff. That morning, I had just been up in my attic which I access by crawling up a rickety, steep staircase inside a closet. It’s easier to get stuff up there than it is to get it down. There are boxes and boxes of receipts and invoices from over ten years ago, there are window fans, old useless canvas suitcases that don’t have spinning wheels, obsolete computer monitors – even an old Apple Mac, one of the originals.

So, when my neighbor called me over by saying, “You probably don’t need anything,” he was right but I dutifully looked through some books and a large box filled with women’s shoes, size 7. I was intrigued by a pair of silver, high-heeled sandals but I’ve never worn high heels and they were too small anyway.

There was nothing there for me and I didn’t want to tell my partner Ken about it because he collects books. He has a storage unit devoted to books he can’t fit on our bookshelves. But I should talk. How many kitchen whisks or colanders do I really need? How many saute pans do I use, even though each one has its own particular characteristic? What about all the empty jars waiting for just that right time to fill them with leftovers? How many do I need?

I haven’t read any books by Marie Kondo who launched a huge movement of cleanup. She’s made millions by encouraging readers to fold t-shirts and socks in a certain way to give order to chaos. I am in awe of people who carefully match up their socks and fold them in a ball. My sock drawer is out of control. How many socks do I really need and why do I lose one sock in a pair all the time?

I’m constantly trying to weed away stuff I don’t need but I’m living with a man who loves to have extras of everything. He buys three or four pounds of butter at a time just to make sure we don’t run out. The freezer is overflowing with butter. When he buys a pair of sneakers, he buys two pairs just in case that model gets discontinued. I notice he’s buying duos of books, “Why?” I ask. “For a friend,” he says.

My mother was a pack rat. Strangely for an artist, she never seemed to have any pencils or pens around. I bought her six-packs from the Office Depot but when I visited a couple of days later, they would all be gone. Where to? It was only after she died that I found fifty pencils and pens stashed neatly away at the back of a bottom drawer – never used. She had an old barn in the back and when we cleared it out we found three Weber grills. I think it was easier for her to buy a new one than sort through all the stuff in the barn to find the old ones.

I think back to my days at the Zen monastery. For a week-long retreat we each had a tea cup to use twice a day. The teacup sat upside down on a small white paper napkin. Every time we tipped the cup over to rest on the paper it left a small round stain from the coffee or tea. We didn’t get a new paper every day. Instead, we used the old one and folded it inside and out until it was replaced after four days.

Yesterday I was in a store that specializes in Japanese things: little tiny plates in green glaze called Mei Mei Zara, square cloths for wrapping objects with a pattern of plum blossoms, flower vases, some lacquer objects that were old and chipped, and tea bowls.

One in particular caught my eye. It was a Korean-style bowl with a lovely feel. I could have bought it in a second. It was very wabi with an understated beauty and lack of artifice as though created for eating rice and then found by some tea master and loved for its quiet purity.

One in particular caught my eye. It was a Korean-style bowl with a lovely feel. I could have bought it in a second. It was very wabi with an understated beauty and lack of artifice as though created for eating rice and then found by some tea master and loved for its quiet purity.

But I don’t need any tea bowls. I have a number of them that have been given to me over the years which I store away in their wooden boxes and bring out for special occasions. There’s a blue Mino glazed tea bowl with a white enso circle on the front which was given the name “Toy with Flowers.” I have another bowl I found when I was in Japan at the Toji market. It’s a Hagi bowl with a creamy, faint pink glaze and it reminds me of that wonderful trip.

While the Korean bowl in the Connecticut shop was fantastic, it was also very expensive – and I didn’t need it. What is enough? Until I make tea for friends at least once a week I won’t collect any more utensils. The few bowls I have are perfect.

One of the great aspects of a tea gathering is that it’s a one-time event. It will never be repeated. The guests will not be the same, the seasons and therefore the objects in the room including the scroll which sets the theme, will never be the same. At the end of the gathering, everything is put away in their boxes and stored until the next time. The tea room is empty, waiting to be filled not with more stuff but with particular favored objects that are filled with meaning and beauty.

Perhaps this is the quality of beauty that we’re looking for. A beauty in our lives that is sufficient as it is.

Aki no koe – the voice of autumn

It’s the first week of August in the Hudson Valley and the crickets have begun to sing. Their song surrounds the Tea House in waves, as though we’re floating on an ocean of cricketing.

Their song is the voice of autumn and reminds me of this phrase from the Cold Mountain Poems of Han Shan.

Crying in the dew, a myriad of grasses

Singing in the wind, a single chorus of pines.

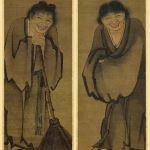

Cold Mountain is a collection of 310 poems written twelve hundred years ago on the rocks, trees, and temple walls of China’s Tientai Mountains. Han Shan and his friend Shi-de (Japanese: Kanzan and Jittoku), active in the late 8th-early 9th century, were Zen Buddhist monks. Han Shan was a hermit and he begged for food at temples, often sang and drank with cowherds, and became an immortal figure in the history of Chinese literature and Zen. Shi-de was Han Shan’s constant companion, and the temple’s janitor. He is usually depicted carrying a broom. They appear frequently in Zen paintings, representing the rejection of the secular world and the search for enlightenment.

They are quintessential Zen men, usually laughing together, wandering carefree, and enjoying each moment as it is.

Gary Snyder, one of the first Americans to go to Japan to study Zen in the fifties, translated the poems in his book Rip Rap and Cold Mountain Poems. They were the first Zen poems I ever read.

I wanted to be Han Shan. I wanted to live as he did. It was the 70s and my friends and I left the cities, regular jobs, and normal lives. Some of us lived in teepees nestled in alpine meadows, others lived in cabins that lined the side of a dirt road in an abandoned logging camp high up in the mountains. I looked for an old cabin on the back side of Ajax Mountain in Aspen so I could live far from the world like Han Shan. I dreamed I would hike in my food for the week and heat the cabin with wood gathered in the summers. Like Han Shan’s home, there would be a one track path to my place. In the mountains the vastness of space and light gave me a glimpse of something I longed to know more of. If I lived like Han Shan I might find it.

I was eighteen. Out of school. No money. My mother said “Come back home. You can’t live a life of Zen out there.” Or maybe she said, “You can’t live a life of Zen.” At that time I had no idea what Zen was, nor did she. I came home to the city, got a job and eventually found my way to NY Zendo on the upper east side of Manhatten. As soon as I sat down on the cushion, crossed my legs, and breathed into the the deep silence I knew this was what I was looking for. It was home. It was Cold Mountain.

The path to Han-shan’s place is laughable,

A path, but no sign of cart or horse.

Converging gorges – hard to tracec their twists,

Jumbled cliffs – unbelievably rugged.

A thousand grasses bend with dew,

A hill of pines hums in the wind.

And now I’ve lost the shortcut home,

Body asking shadow, how do you keep up?

Mono no aware

Sei Shonagon’s writings are filled with what the Japanese call “aware,” a poignant nostalgia for the past. It’s a melancholy, sweet ache that is almost beautiful. I feel it strongly in the late summer with the appearance of the crickets and cicadas in my garden. Summer is fading and soon we will be entering the long dark evenings and short cold days of winter.

I went away in the midst of this summer for three weeks. I knew the garden would grow unruly without my daily care but I didn’t think it would be too much, so I wasn’t worried. Before leaving, I cleaned the house and then went out to the Tea House. In the summer, if it’s humid, the tatami mats get moldy – green slimy mold on them, so I set the ceiling fan on low and removed the scroll that was hanging in the tokonoma alcove. I rolled it up and brought it inside my house where it was sure to be safe. The Tea House was bare and empty.

When I returned from vacation, the garden had grown more wild than I ever expected. It had rained constantly throughout July, something it hadn’t done in years. Weeds were three feet high, the grass had to be weed-whacked before it could be mowed. In Switzerland, where we had gone hiking near the Eiger Mountain in the Bernese Alps, I saw an old woman with long gray hair scything her small field. That was me back home with my weed whacker.

The hot, rainy month of July has ended and now in an unusual cooling with the full moon the crickets have started their mating with sounds like waves of chirping in the long deep slide from late evening into darkness.

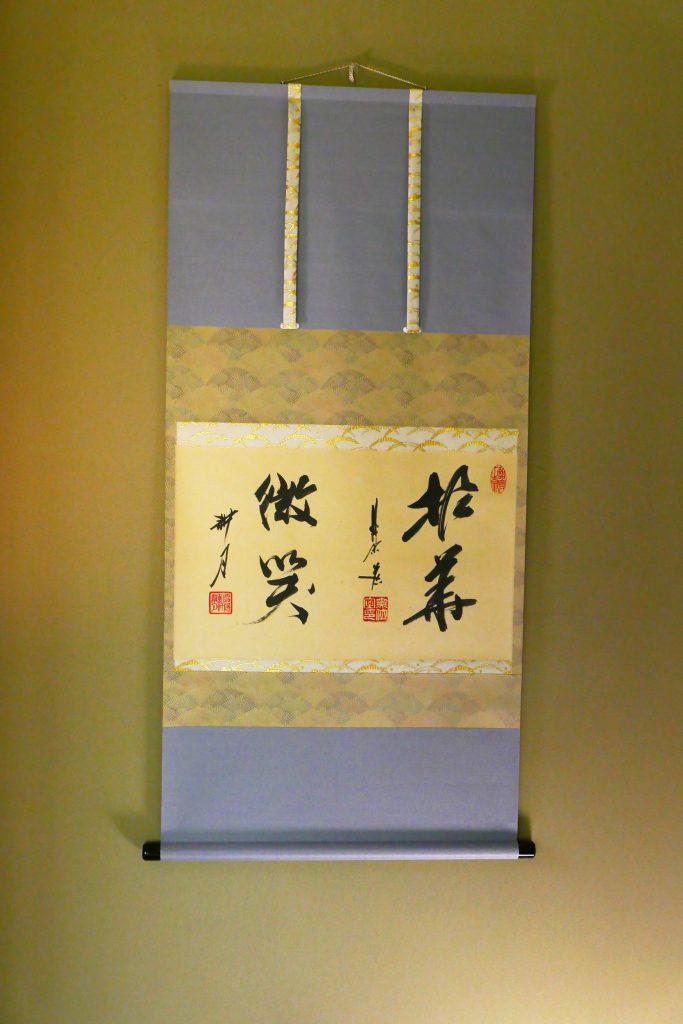

I went out to the Tea House and opened all the windows and turned off the fan. The space felt empty and I realized that what makes it vibrant and alive besides the incense and people sitting together is the scroll, the calligraphy in black ink drawn by my teacher and other Zen masters. I’m lonely without them.

I look for a scroll. Which words do I choose to convey this sentimental melancholy that I’m feeling? Who do I turn to? I miss my teacher who died five years ago. I pick a scroll that he had mounted for me. I hang it in the Tokonoma and sit down.

It reads, “Holding up a flower. Subtle smile.”

The space returns to its vibrancy, its depth of purpose. This is no ordinary space, it is a place that confirms and supports truth. The gold thread sewn into the cloth mounting around the white paper of the calligraphy shimmers in the shadows of the early evening.

I weep for the intensity of my training practice. My life. Now more ordinary without my teacher.

But when I hang this calligraphy of his, his spirit comes alive as he was, and it says, this is the way and I offer it to you, ordinary yet beyond time and place.

Ranjatai Incense

I searched all over Kyoto to find the same incense that had been given to me years before on my birthday. The delicate fragrance had scents of sandlewood, spices of cinnamon and clove, and camphor.

In the practice of tea, incense is prized and at some tea gatherings the host will bring out various incense for the guests to appreciate. It’s called “Listening to incense.”

The most highly prized and rare incense is called Jin-koh, also called Agarwood, that comes from Southeast Asia. It’s literally worth it’s weight in gold. Agarwood forms when Aquilaria trees become infected with mold and the tree develops a resin to protect itself. This resin forms in the heartwood of the tree and is what is prized as Agarwood or Aloeswood.

The largest piece of Jin-koh in Japan was given to Emperor Shomu (AD 724-748) as a tribute from China. It has been kept in the Imperial treasure repository since that time. It is named Ranjatai and is the most famous chunk of wood on the planet. It weighs 11.6 kilograms and is 1.56 meters long.

For the past millennium, only a few small pieces have been cut from the Ranjatai.

For the past millennium, only a few small pieces have been cut from the Ranjatai.

In 1465, one small piece was ordered by Emperor Gotsuchimikado as a gift to Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. In 1574, a small piece was given from Emperor Oogimachi to general Oda Nobunaga for his efforts in unifying Japan, In 1602, Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was powerful and influential enough, obtained a piece, and in 1877, Emperor Meiji asked for a piece.

That’s how coveted this piece of wood is.

Nobunaga kept his small piece and then gave fragments of it to two guests who came for a tea gathering. This gift demonstrated his cultural superiority and power. The two guests received Ranjatai fragments presented on open fans. The fans were decorated with cut gold foil.

Every ten years Ranjatai is brought out of the treasury repository and exhibited. People line up for hours to view it – the most famous piece of incense in the world.